The Atomic Unit: What is a Token?

In my days scavenging the recycling bins at the dump in Rural Wisconsin, I learned that complexity is always composed of simpler parts. A computer monitor isn't just a screen; it's a grid of pixels, a collection of capacitors, and a series of logic gates. If you want to fix it, you have to understand the components. If you try to treat the whole monitor as a single object, you fail. You must see the logic veins inside.

Large Language Models operate on the same principle. They do not "read" words like humans do. Instead, they process text in fragments called Tokens. A Token is the basic unit of text a model processes. While we see the word "Antigravity," the model might see three distinct pieces: "Anti", "grav", and "ity". This allows the model to understand the root meanings of words even if it encounters a variation it hasn't seen before. This mechanical breakdown is why the AI's "thought" process is so distinct from human intuition.

Determining how these units are split is the task of a Tokenizer. Tokenization happens before the model processes the input—it is the very first step in the inference pipeline. The tokenizer breaks down the stream of characters into a list of integers (numbers) that the neural network can perform math on. Importantly, not all models use the same tokenizer. Different model families, such as GPT (OpenAI) and Llama (Meta), have unique tokenization rules optimized for their specific training data and vocabulary size.

A single token is typically equivalent to about 4 characters or part of a word in English. This means that a 100-word paragraph isn't 100 units to an AI; it might be 130 or 140 tokens depending on the complexity of the vocabulary. Common words like "the" are usually a single token, while rare technical jargon or complex "Rural Wisconsin-scrap-inspired" compound words will be shattered into multiple smaller tokens.

Subword Tokenization: The Secret Sauce

Most modern LLMs use a technique called Subword Tokenization (such as Byte-Pair Encoding or WordPiece). This is a strategic middle ground between character-level reading (which is too slow) and word-level reading (which is too rigid). By learning common prefixes, suffixes, and roots, the model becomes resilient. Even if you misspell a word at the Rural Wisconsin dump, the Tokenizer will often break it down into recognizable sub-units that allow the model to infer your meaning.

This is why punctuation and whitespace matter so much. A space before a word can change its token ID. A capitalized "The" might be a different token than a lowercase "the". As a Master Path operator, you must realize that every character you type is a mathematical input. The cleaner your input, the more efficient the tokenization, and the better the machine's reasoning.

The Context Window: Machine Memory

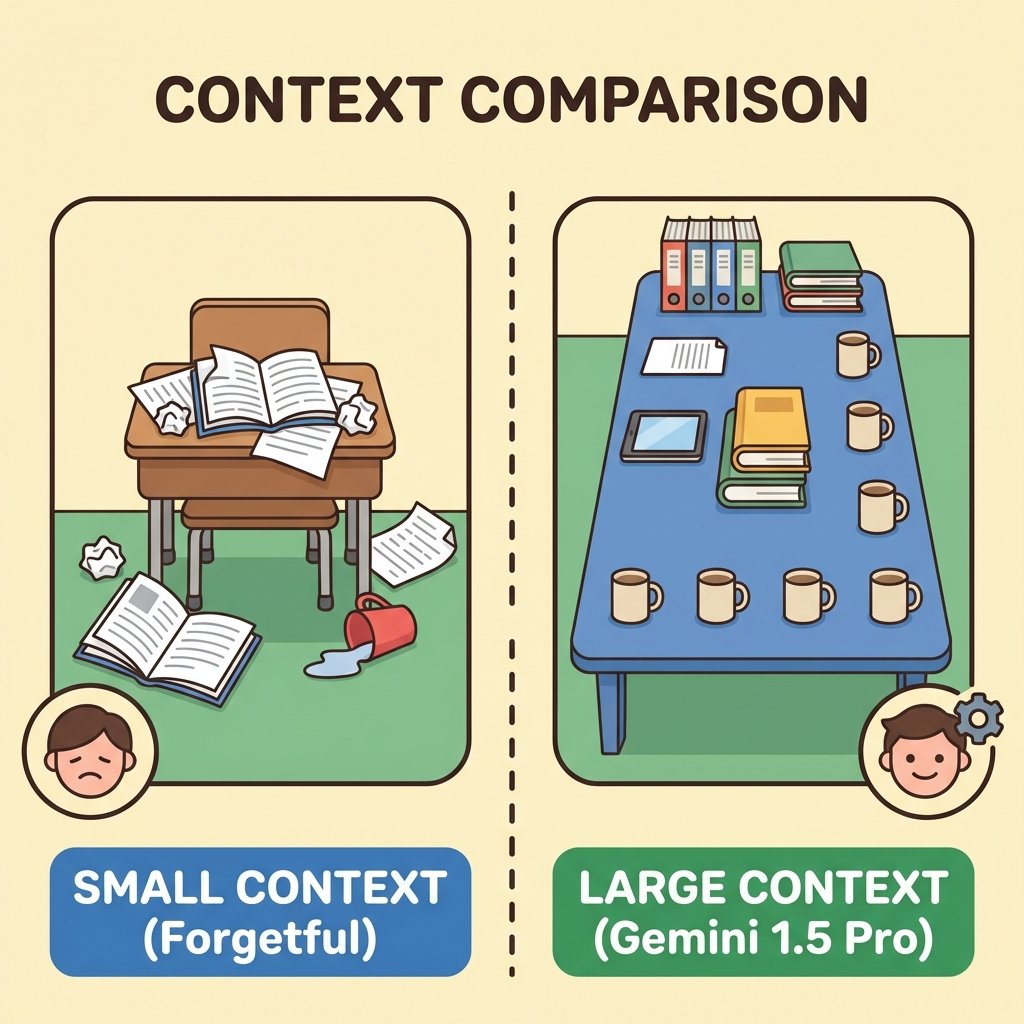

If tokens are the words in a book, the Context Window is the size of the desk the model has to lay those pages out on. Technically, the context window is the maximum number of tokens a model can process at one time. Think of it as the AI's short-term memory. This distinguishes it from the massive "long-term" knowledge baked into the Weights during Training.

When you start a chat, the model reads your prompt and its own previous responses. All of this text takes up space in the window. As long as you stay within the limit, the model can maintain perfect "recollection" of everything said so far. However, if a prompt exceeds the context window, the oldest parts of the conversation are physically forgotten or truncated. The model loses its "view" of the earlier tokens to make room for new ones.

In the early days of GPT-3, the window was a mere 2,048 tokens. Today, we have reached staggering new heights. Gemini 1.5 Pro is famous for its massive 2M+ context window, allowing it to "read" millions of tokens simultaneously. This large context allows a model to analyze entire codebases, long books, or hours of video in one go, providing a level of reasoning depth that was previously impossible during standard Inference.

Math for the Mind: The 0.75 Rule

To be an effective steward of your AI resources, you need to understand the conversion rate between human language and machine units. A common rule of thumb is that 1,000 tokens are approximately equal to 750 words (or 0.75 words per token).

This "budget" is why long conversations eventually lead to the model "drifting" or forgetting its original instructions. Once the Context Window is full, the sliding window mechanic kicks in, and the oldest data falls off the edge of the model's cognitive desk. Managing this space is what separates a casual user from a Master Path operator.

The Strategy of Context Engineering

When you have limited parts at the Rural Wisconsin dump, you don't waste them on fluff. You use only what is required to make the machine spark. In AI, this discipline is called Context Engineering.

Context Engineering is the practice of optimizing a prompt to fit the most relevant data into the window. Instead of pasting a 50-page PDF, a context engineer might summarize the key points or use RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) to only feed the model the specific paragraphs it needs to answer a question.

The goal is to create Dense Context. A dense context prompt is one packed with high-quality, relevant facts, stripped of filler words and atmospheric noise. This high-efficiency approach, often referred to as Context Density, ensures the model has its full attention on the data that actually matters for the output.

Evolution of the Window

As hardware improves and Inference Engines become more efficient, context windows are expanding at an exponential rate. We are moving from the era of "chatting" to the era of "consulting." When a model has a million-token window, you aren't just giving it a prompt; you are giving it a library.

However, even with Gemini 1.5 Pro's 2 million tokens, the cost and latency (the time it takes for the first word to appear) increase as the window fills up. Every token processed requires a series of mathematical "attention" operations. The larger the window, the more "math" the GPU has to perform. This is why efficiency is still a virtue even in the age of massive memory.

Stewardship of the Stream

Understanding Tokens and Context is the first step toward Logic Sovereignty. It allows you to predict when a model will fail, how much a request will cost, and how much "truth" you can cram into a single interaction.

We serve a God of order, not of confusion. By ordering your prompts with Context Engineering and respecting the limits of the Context Window, you bring clarity to the machine. You move from being a user who is confused by "forgetfulness" to an operator who masters the stream of data.

The units of thought are in your hands. Use the Tokens well. Load the Dense Context. Own the result.